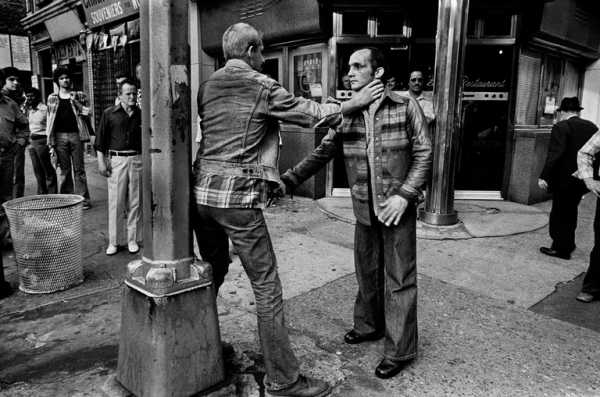

Street photography has always been a predatory enterprise. Traditionally, the intrepid photographer sets out on the streets as if on safari, picking off prey with a camera unobtrusive enough to not raise the hackles of the local wildlife. (The 35-mm. Leica, introduced, in 1925, at the Leipzig Spring Fair, practically produced the genre, due to its then-novel portability, low profile, and whisper-quiet shutter.) Bruce Gilden, however, has made a name for himself by getting in people’s faces. When he stalks the streets, it is often with a blinding flash attached to his camera, which he’ll pop off at an arm’s length from his subjects, petrifying them in the glare. To extend the safari metaphor: this is akin to dismounting from your jeep and gambolling over to a lion so you can play a game of amateur animal tamer. Remarkably, he did this in New York in the nineteen-eighties. Gilden certainly had some gall.

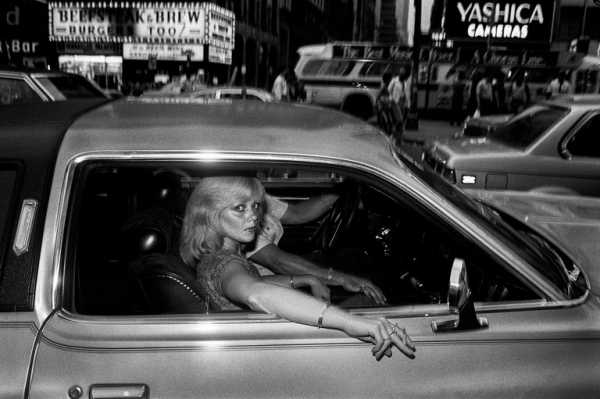

Gilden’s new book, “Lost and Found” (Éditions Xavier Barral), is, in fact, an old book of sorts. In the introduction, he recounts that after decamping from his apartment in New York City and ending up in the comparatively greener pastures of Beacon, he stumbled across a personal treasure trove. Tucked away in his archive were more than two thousand rolls of film from the nineteen-seventies and eighties, which had for some reason slipped through the cracks. During the summer of 2018, Gilden mined these forgotten veins of his work and came away with a collection of seventy-five gritty street snaps from New York’s shambolic “Taxi Driver” era. (An apt reference, it turns out, because Gilden drove a taxi around the time he was making at least some of these pictures.)

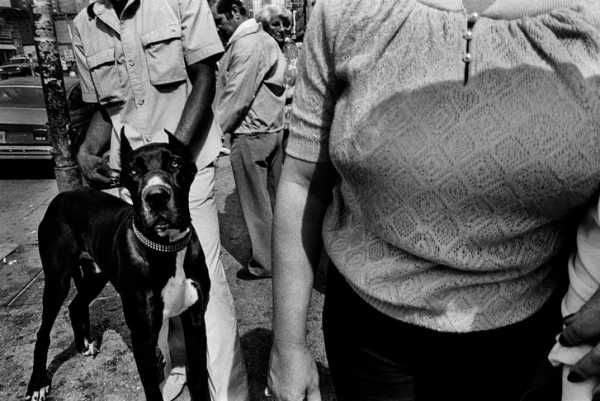

“I like to say that street photography is when you can smell the street and feel the dirt,” Gilden writes in his introduction, “and that’s what you feel in these pictures. You feel the dirt, you feel the sweat, you feel the sleaziness, you feel the tension, you feel . . . New York.”

He’s not lying. The vibrance and squalor of the city in the seventies is spread across these pictures like a greasy film. You almost get the sense that you could swipe a finger across them and leave a mark. All of the archetypes present themselves for roll call: the two-bit hustlers, the hard-knuckled mafiosos, the spinsters in their smocks, the poor and the beaten down, the unconscionably rich.

Of course, street photography is not census-taking. To be good, it must be built on moments—the eruption of the theatrical, the fortuitous, or the inexplicable, into the humdrum everyday. Sure enough, Gilden’s got moments to spare. Look: a man caught in the act of grabbing another man by the throat, which would alarm were it not for the eerie, inexplicable placidity of his victim’s face. Look: a forlorn man packed in a scrum of pedestrians, a coat wrapped around his head like a nun’s habit. Look: three men with hairlines heading for the hills, wearing nearly identical suits. Look: three women—perhaps, we could imagine, those earlier three mens’ wives—with ridiculous cotton-candy coifs, decked out in furs, each finer than the last. Look: a man stopped on a street corner, standing stork-like on one leg, his foot temporarily unshod as he tugs up a drooping sock.

Like Garry Winogrand, who is perhaps Gilden’s closest photographic cousin, his eye can sometimes be plain mean. A grimacing woman with a scrunched-up nose barges into the frame; an aging gigolo type, all polyester, gold-plated jewelry and swagger, stands with his scowling wife gripping his arm—such subjects raise the suspicion that they merited the camera’s attention principally to be the object its ridicule. Gilden’s later work, unrelenting closeups of poverty-ravaged faces, lit with direct, powerful flash, seems to provide corroborating evidence. Although they ostensibly traffic in a kind of warts-and-all honesty designed to confront us smugly with the world as it is (call this, perhaps, the Arbus School of Visual Aggression), the pictures noticeably lack the kind of weather-beaten dignity that, say, Katy Grannan bestows on her subjects.

Even with these rough edges, Gilden’s pictures shine as prime examples of a photographic mode that has all but disappeared. The street, it would seem, no longer calls to photographers as it once did. But why? After all, as anyone who lives here knows, New York has no shortage of drama on its sidewalks and in its subways. With the right eye, surely someone could again make the kinds of pictures that Gilden unearthed from his archives, and give the genre his or her own idiosyncratic spin. It seems, though, that the motivation has been lost. Perhaps the explanation is simple: while the streets might still be a circus, we no longer think of them as the biggest stage upon which we strut and fret our hours. Instead, we have vanished into our virtual worlds, halls of mirrors from which it is becoming ever more difficult to escape.

Sourse: newyorker.com